What is a Warrant? It’s unusual, in today’s world, for an investor or a company seeking funding, to have heard of the term “warrants”. That’s a shame as warrants can be a tremendously advantageous tool for both parties. Even though warrants have been around for hundreds of years, they are one of the lesser-known tools that can give the investor and the business some flexibility. We are going to describe the advantages and disadvantages of warrants from both the company’s viewpoint as well as the investors. The good, the bad, and the ugly. The goal here is to demonstrate that a warrant can be an excellent tool in the kit to entice investors by providing a good upside while allowing the company to get funding, and why Tidewater usually asks for them when we make an investment. First, the Basics What is this thing calling itself a “warrant”? Let’s start there. A warrant is a contract that grants someone the right to buy shares of the issuing company’s stock, at a specific price, before an expiration date. The contract is issued by the company, bought by an investor, and allows the investor the legal right to demand that the company send him the specified shares listed in the warrant before the warrant “expires”. Also, the company can charge a fee for the warrants. Usually a small amount per warrant, especially since they are typically issued in large amounts, up to millions of warrants as we’ll see later. We will cover the math that’s used to price warrants in a moment. As an alternative to just paying cash for the warrant, the company may just issue them as an incentive for investors for some other type of funding, such as a line of credit, or convertible note. After they are issued, warrants may be traded on the public stock markets, or just between investors in private transactions, or even the company itself might buy them back from the investor. Another way of saying it is the warrants are fungible and can be freely traded. Companies issue warrants only for their own stock or that of subsidiaries whereas an investment business can issue warrants for any publicly traded stock, regardless if they actually own the stock. Why would a company issue these things? Company’s typically issue warrants as a “sweetener” as part of some other transaction, such as raising capital through a bond offering, or maybe when an aggressive investor asks for them when providing some sort of other investment such as a line of credit, or some type of loan like a bridge or mezzanine. You could say it is a type of add-on that helps secure the actual investment. Warrants Have Four Components There is a time limit, a conversion ratio, a purchase price for the warrant itself, and a “strike” price (the price of exercising the warrant and obtaining actual shares).

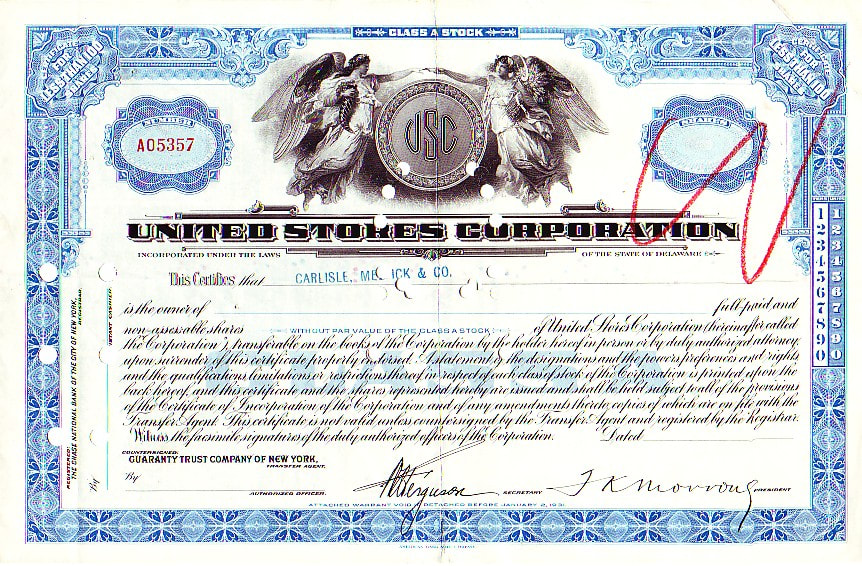

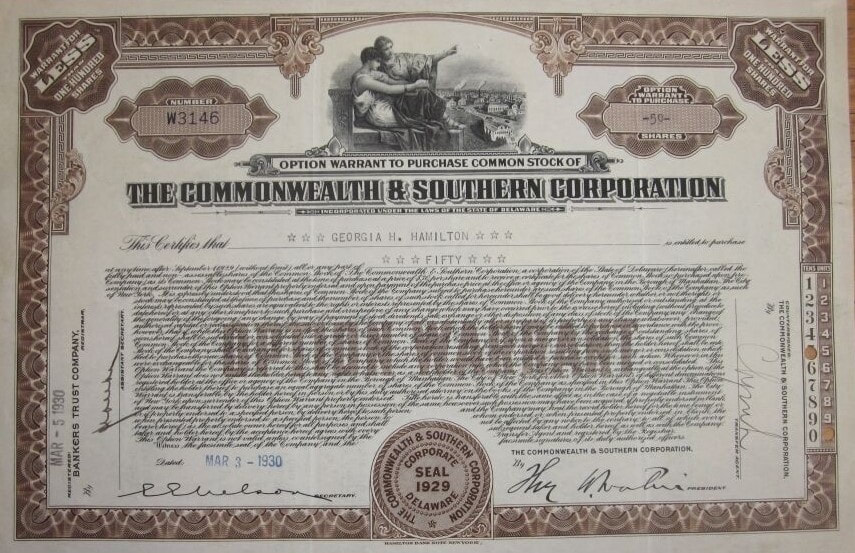

The Math Let’s work out the math. In this example the successful company, with plenty of customers and revenue, has a price of $50 a market-based price per share and the warrant strike price is $40 a share. (Obviously, the investor isn’t going to pay a nominal amount like a penny to purchase these warrants.) Subtract the exercise price from the market price to find the intrinsic value of the warrant. This gives you an intrinsic value of $10 per share. Divide the intrinsic value by the conversion ratio to find the value of one warrant. In this example, if the conversion ratio is, say, five-to-one, you have $10 divided by five. One warrant is thus worth $2, and the investor has to include a check or some form of payment of $2 per warrant when he buys the warrant. Afterward, he can also sell the warrant to someone else for $2 each, or more, if there’s growth in the business. Then, down the road at exercise, he would pay the strike price of $40 a share, collect the shares and hope they move up beyond $50 as that’s his break even in our little example. What if the market price was $75 or $100 when he exercised the warrants? The investor can tap dance all the way to the bank! But, if the market price is less than the exercise price, the warrants have no value because you could buy the shares on the market for less. Warrants acquire value only if the market price is above the strike price. But, imagine for a moment, that the price of the stock was, say $65 a share! The investor just got an immediate profit of $15, or 30%, assuming they turned around and sold them. Now let’s pour some gasoline on the fire! Imagine the stock was $65 a share and the warrant has a $40 strike price? What would the warrant be worth before he exercised it? Glad you asked. The intrinsic value of the warrant would now be $25. Using the same 5 to 1 conversion ratio, each warrant would now be worth $5 each. So our original investment went from $2 per warrant to $5 per warrant! That’s 250% gain. Now imagine having the foresight to buy 5,000 warrants for $10,000. That would be worth $25,000 in warrants. If you had no interest in the actual stocks, it’s possible that the company will buy them back from the investor and retire them unconverted. How an Angel Investor Operates Since I’m an Angel investor, and the companies I invest in are usually fairly new, or not yet profitable, both the purchase and strike prices are usually nominal. Something like the 1/100th of a cent. That means when the company accepts whatever the investment is, a convertible note, a line of credit, etc, I will ask for warrants at a nominal strike value and my cost for each warrant is technically zero. Obviously, the company isn’t going to issue them without getting something in return, like a convertible note. Hopefully, the company doesn’t go bankrupt and they’ll become valuable down the road. That’s the risk for me and yes it happens. It’s actually a compliment to the business that the investor thinks there’s enough promise there to want the stock years off. An Example Here’s an example of a warrant issued in 1966 for 10 shares of common stock in a company called General Acceptance Corporation. Notice that the expiration date is for June 14, 1976. With a ten-year expiration and an exercise price of $21.50 per share, the investor would have to write a check for $215.00 to the Warrant Agent and send in this certificate to actually receive the share certificate. Remember in 1976, $215 dollars was nothing to sneeze at. Hopefully the investor saw the share price climb far about $21.50. The Warrant Agent (the financial business that handles the actual warrants and shares) is Chase Manhattan Bank. Notice there is a company seal affixed, with appropriate signatures of the President and banker. Most modern warrants don’t have these beautiful (and often collectible) certificates. Today they’re just plain sheets with the words typed out by the corporate counsel. Warren Buffett and Bank of America Many, many people use warrants today. You just don’t hear about it. In Hong Kong and Europe warrants make up a sizable portion (over 10%) of the trades on the public exchanges. Many C.E.O.’s use warrants as part of their incentive package. The highest profile person, in the last 50 years, to use warrants is Warren Buffett. He was called upon to help Bank of America during the 2009 government-caused housing debacle. The bank had an issue of not having enough cash on the books for its liabilities and the federal government takes a dim view of that. Rumor has it that he was asked by the feds to “help”, so he structured a deal that really favors himself. Read the details about it here… http://investor.bankofamerica.com/news-releases/news-release-details/berkshire-hathaway-invest-5-billion-bank-america/ …CHARLOTTE, N.C., Aug 25, 2011 (BUSINESS WIRE) -- Bank of America Corporation announced today that it reached an agreement to sell 50,000 shares of Cumulative Perpetual Preferred Stock with a liquidation value of $100,000 per share to Berkshire Hathaway, Inc. in a private offering. The preferred stock has a dividend of 6 percent per annum, payable in equal quarterly installments, and is redeemable by the company at any time at a 5 percent premium. In conjunction with this agreement, Berkshire Hathaway will also receive warrants to purchase 700,000,000 shares of Bank of America common stock at an exercise price of $7.142857 per share. The warrants may be exercised in whole or in part at any time, and from time to time, during the 10-year period following the closing date of the transaction. The aggregate purchase price to be received by Bank of America for the preferred stock and warrants is $5 billion in cash. Let me explain what happened. Mr. Buffett wrote the bank a check for $5 billion…in cash. That is what they needed, and they happily cashed that check. In turn, the bank created a special class of preferred shares paying a 6% dividend, just for Warren. What’s 50,000 times $100,000 each? Why that’s $5 billion. So, while Mr. Buffett waited for this to pay off, he made 6%, or $300 million, in dividends! Six years later, in 2017, upon passing an annual Federal Reserve stress test, the bank was given more latitude to raise its common shares dividend. Management did so, increasing its annual dividend on common stock to $0.48 per share, above the $0.44 threshold that would have equaled the 6% yield Mr. Buffett was earning on his preferred shares. Since he could receive a larger annual payout from Bank of America's then-current common stock dividend than its preferred stock, he converted his preferred stock for 700 million common shares by exercising his warrants. That’s how he paid for the warrant shares. He could have written them a second $5 billion check too and kept the preferreds if he had wanted. At the 6% dividend, Mr. Buffett was making about $300 million a year. After the bank raised the dividend on the common shares, he converted the preferred into common by exercising the warrants and then started making $330 million in common dividends. The warrant to purchase 700,000,000 (that’s seven hundred million) shares of common stock within a ten-year window at a price of $7.142857 comes out to exactly $5 billion. He also kept his $1.8 billion in dividends he made over the 6 years he held the preferreds. When he decided to exercise the warrants in late 2017, the stock price was at $24.32. An instant profit of $17 billion dollars, plus his original dividends of $1.8 billion. Remember, he only paid $5 billion to start with. Pretty shrewd maneuver for Mr. Buffett. Warren Buffett and Goldman Sachs But Mr. Buffett wasn’t done. He saw another opportunity to “help” the great Goldman Sachs with a similar setup. Here are the highlights… https://www.nasdaq.com/articles/warren-buffett-converts-crisis-era-warrants-28-goldman-sachs-2013-10-09 Again, he wrote a $5 billion dollar check to Goldman and received millions of perpetual preferred shares paying a sweet 10% annual dividend. That’s a cool $500 million a year. But he wasn’t satisfied with a measly $500 million a year. He convinced Goldman to also issue him warrants for 43.5 million common shares. On the preferred shares, Goldman had the right to buy them back, and did so in March 2011, paying Mr. Buffett $5.64 billion. That included the original $5 billion in principal, as well as a $500 million bonus for early repayment, and $140 million in dividends Mr. Buffett was due. So, he made $640 million on his $5 billion investment, or about 13% over two-and-a-half years. Not bad. But Mr. Buffett was also collecting dividends while he held the shares, amounting to roughly $1.1 billion. All in, he made about $1.75 billion, a 35% return on his preferred share investment. The warrants had a surprisingly good payback too. Mr. Buffett didn’t exercise them but waited for Goldman to rise much higher. It did but he held out converting. But the big boys do things a little differently than we do. Goldman ended up renegotiating the prospective purchase before Buffett had a chance to pull the trigger, replacing it with terms that were very profitable and less complicated for both parties. Berkshire was granted 13.06 million Goldman shares and $2 billion in cash. And the really great part, for Mr. Buffett, was this new deal didn’t require him to put up any new cash to convert the shares. Goldman convinced him to take 13 million shares and a couple billion in cash and give up the rest of the warrants! So, he got billions of dollars in value at no cost to him. To say it another way, Mr. Buffett gave up his right to purchase the difference of 30.44 million shares. For that, he got a payout of $2 billion in cash and over 13 million shares for free. Altogether, he paid out $5 billion, and got back $7.64 billion in cash, plus 13 million Goldman shares. There’s a reason he’s called the Oracle of Omaha. Advantages for the Investor Sometimes warrants are fabulous investments for the investor. It doesn’t take a genius to realize it’s a good thing when you’re going to be getting shares of a business for a hundredth of a cent! What a great deal, especially if the price of the stock rises to two dollars, or ten dollars, or more in a few years. That is the number one advantage for the Angel investor, the fact that he has gotten in at the absolute rock bottom. Imagine buying Netflix warrants at $.09 and having it rise to over $400 per share in July of 2018! Of course, most people aren’t so farsighted and a money losing company usually isn’t attractive as an investment. So, the advantage for the investor may be a tremendous upside at some point down the road. And don’t forget that the investor does not ever have to exercise them if the company’s stock price isn’t high enough to be profitable. Disadvantages for the Investor What could possibly go wrong our plan? Nothing. The plan is fine. It’s the business that might give us some trouble. They might go out of business, not make a profit, or only make a tiny profit, for a long time. None of those scenarios will do much for the investment thesis of the company, nor the bank account of the investor. So, a word of caution is necessary here. The investor should be exceptionally comfortable with the prospects of the business. This is why warrants are usually not asked for when the investor is an Angel investor, or the company is very early in their life. On the other hand, I sometimes will take that risk especially if the business and the founder show good promise. Sometimes I’ll lose, sometimes I’ll win. We all know the risk is pretty high for an investor that any new business will go under and the warrant certificates will be fodder for the fireplace. But, if the investor is confident enough in the business to make some sort of investment such as a line of credit or a convertible note, they obviously should have some reasonably good idea about the future of the enterprise and the capabilities of the C.E.O. In that case the investor can ask for warrants to give him a nice “extra” pop down the road. Which leads us to discussing the good and bad for the business. Advantages for the Business Why would a business offer warrants to someone? I can think of two reasons. The first is to entice the investor into making the main investment – convertible note, bridge loan, and so forth, and getting a better deal than without the warrant. Say, a lower interest rate on the note or bridge. The prospect of making an easy buck down the road for a very small dollar amount today might be just the ticket to finalize the deal if the investor is on the fence. The second reason is cost. Or rather, the lack thereof. It costs the business nothing, except legal fees, to write the documents and issue warrants. No actual money or shares will trade hands until the investor exercises the warrants. That might not happen for years. Can you see why new companies should really start using warrants more? It can be very advantageous for businesses to go down this path. When a warrant deal is reached by the company and an investor, the actual shares have to be issued. There is usually a resolution by the board, and a capitalization chart entry to show that shares issued, to mean they exist, but owned by no one. They are in “reserve”. Any shares in reserve (also called “held in treasury” or “treasury shares”) are like they don’t even exist because voting rights are based on outstanding shares. You could always play with warrants to give voting rights, but you normally don’t, it just confuses everyone. Shares being issued and held in reserve dilute no one. They only dilute people when the issuer passes them on to a buyer/shareholder. The corporate counsel will keep track of all this in the corporate logbook. Disadvantages for the Business It isn’t all peaches and cream. Of course, there’s some disadvantages for the business. Actually, there is only one disadvantage. When the warrants are exercised, everyone who currently owns shares will then get diluted. It might only be a trivial amount, but they will get diluted in their ownership percentage. That may not sound very pleasing to prior investors at all. If one or two of them were large investors, they may try and block the process. It just depends. I have had founders who didn’t really understand warrants, go, and ask other investors what they thought. You know the answer. It’s a no. Sadly he didn’t understand what I was offering. Those Pesky Laws and Other Details In case you are wondering, the Securities and Exchange Commission considers warrants a form of “securities” and they fall under their authority. That means everything you do regarding warrants has to follow well established legal rules and laws. The S.E.C. has no sense of humor if you don’t follow their rules. This means that you will need a great business attorney who understands warrants. Wall Street is full of extremely intelligent people. Some of the smartest people in the world work in finance. That also means they continually invent new and exciting “products” to sell to the rest of us. The standard usage of warrants is a “call” warrant and what we’ve been discussing. A call warrant that allow the holder to force the issuer to create and issue shares when the warrant is exercised. A “put warrant” will force the issuer to buy shares owned by the holder. Traditional warrants are often issued in conjunction with bonds, which in turn are cleverly called warrant-linked bonds, as a sweetener that allows the issuer to offer a lower coupon rate. These warrants are often detachable, meaning that they can be separated from the bond and sold on the secondary markets before expiration. A detachable warrant can also be issued in conjunction with preferred and common stock. Wedded or wedding warrants are not detachable, and the investor must surrender the bond or stock the warrant is "wedded" to in order to exercise the warrants. So far, we said only the company can issue warrants for its stock. Covered warrants can be issued by any financial institution rather than companies, so no new stock is issued when covered warrants are exercised. Rather, the warrants are "covered" in that the issuing institution already owns the underlying shares or can somehow acquire them if the warrant holder wishes to exercise them. Finally, the underlying securities are not limited to equities, but may be currencies, commodities or any number of other financial instruments. That’s right, a warrant can be issued on just about any type of thing that has value that changes over time. Warrants for a ship load of crude oil or a train load of corn? Yes, they are out there. There are another 3 or 4 types of warrants that don’t have any meaning to us as they exist only where a warrant is created specific to the deal. Don’t forget about the tax man. Taxable consequences from the use of stock warrants depend on how they're used. The taxes that may be attached to a stock warrant can be complicated; they are usually taxed once the warrants are exercised. Here’s another example from 1930. Ms. Georgia Hamilton has a warrant for 50 shares of The Commonwealth & Southern Corporation. Notice the pretty corporate seal. On the left side we see the Warrant Agent, Bankers Trust. The fancy lettering makes it hard to read unless you had the page in your hand, but the title is easy to understand – “Option Warrant To Purchase Common Stock of The Commonwealth & Southern Corporation”. These old warrants are very collectible and make a very nice decoration on an office wall. Conclusion Warrants can be fabulous addon’s to investments, for both parties. It’s an easy tool for a business to offer as an inducement to an investor and the investor can get an outsized return in the future should the business really take off. We should always look for these types of opportunities! But a final word of caution. Don’t try this at home. You absolutely must retain a business attorney (preferably a securities attorney) to create the documents and to manage this process. You do not want to run afoul of any securities laws. Also, make sure your accountant is familiar with the tax rules surrounding warrants and other convertible securities. Who is Tidewater? Tidewater Capital Services is an international, private investment firm based in Charlotte, North Carolina. We manage multiple alternative asset classes, including:

From our beginning, we've been passionate about achieving better results for ourselves and our investments—results that go beyond financial and are uniquely tailored, pragmatic, and enduring. We partner with whom we do business and maintain a shared sense of ownership across all of our investments. Today our core values of Teamwork, Integrity, Accountability, Innovation, and Diversity, remain ingrained in every aspect of our organization. If you are a business owner or executive with an idea that is unique or revolutionary and in need of an infusion of capital, and would like more information, reach out using our Contacts page and I’ll look it over.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorMy name is Lee West. I help people develop their businesses into industry leaders so they can achieve their dreams. Thank you for reading. Archives |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed